- LajmeShqipëri Maqedoni Foleja.com Impresum Shkurt e Shqip

- Op/Ed

- Sport

Futboll Basketboll Sporte tjera- Roze

Arte Muzike Yjet TV/Film AutoTech Fun Shneta- Te tjera

Lajme

Shqipëri Maqedoni Foleja.com Impresum Shkurt e ShqipOp/Ed

Sport

Lajme

string(105) "interview-sanja-ivekovic-i-want-to-be-intentionally-active-not-a-passive-object-of-the-ideological-system"Arte

Donjeta Abazi

06/01/2025 16:14Interview/ Sanja Iveković: «I want to be intentionally active, not a passive “object” of the ideological system»

Arte

Donjeta Abazi

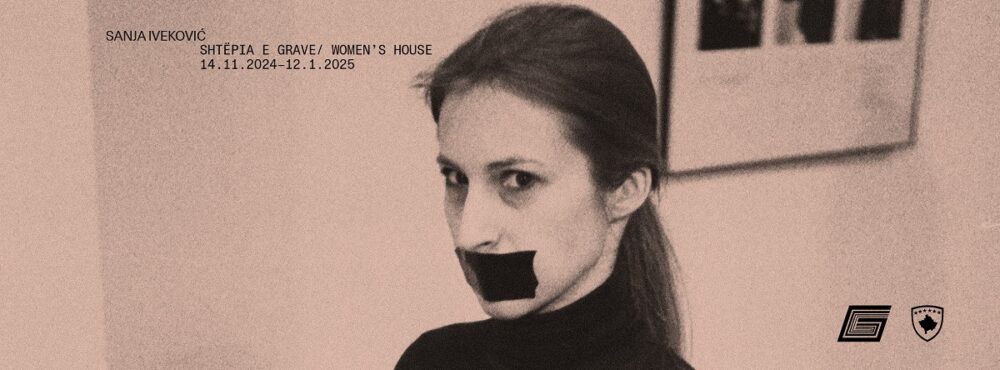

06/01/2025 16:14An interview with Croatian artist Sanja Iveković, who in November 2024 opened her solo exhibition and personal archive, “Women’s House,” at the National Gallery of Kosovo.

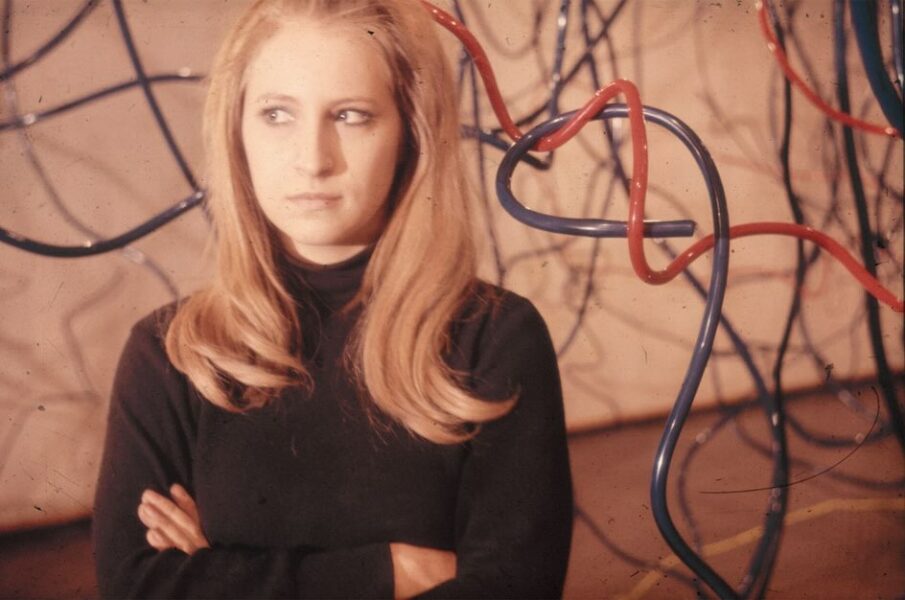

Sanja Iveković (1949, Zagreb) graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts in Zagreb in 1970, when she began to exhibit her artwork. Iveković has exhibited her work at many national and international shows (Paris Biennale, Sao Paolo Biennale, Manifesta, Documenta, Liverpool Biennale, Istanbul Biennale, Prague Biennale and others), and her video works and video installations have been shown at numerous international video festivals (Ljubljana, Berlin, Geneva, Paris, Montreal, Los Angeles, Locarno, Tokyo, the Hague, Osnabrück, Bonn, Dessau, etc). In 2005 and 2006, Iveković resided in Berlin as a German government fellowship (DAAD) recipient. She had retrospective exhibitions at Galerie am Taxispalais, Innsbruck (2001), nGbK, Berlin (2001), Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne (2006), Göteborgs Konsthall, Göteborg (2006), Fundació Antoni Tàpies, Barcelona (2007). Her works are in the collections of many museums including: MOMA, New York; Musée National d’art Modern Centre Pompidou, Paris. In addition to creating art, Iveković also engages in female activism and is a founder and member of several women’s NGOs in Croatia.

Lexo Edhe:

«’The ‘Triangle’ is still interesting; the issue of control over public space is just as strong and present in neoliberal democracy as it was in communism. Today, surveillance has become so “natural” that we hardly notice the ideology behind it»

Gazeta Express: Let us begin with your artistic work, specifically the performance piece “The Triangle”, which was also showcased at the National Gallery of Kosovo as part of your exhibition ‘Women’s House’. This photograph, in particular, carries profound significance, offering a multitude of interpretations. It explores themes such as feminism, revolt, and the rebellion of women against societal and systemic norms, particularly through the medium of art. How crucial is creativity in such forms of expression to encapsulate and convey these diverse interpretations within a single photograph?

Sanja Iveković: Performance “Triangle” is one of my early piece which “survive” with its“meaning” intact outside the specific political situation in Yugoslavia in 1979? I often work with specific contexts, so physical, social and political contexts are my materials. I do not agree with the reading of this work as an act of simple dissidence in a totalitarian context. Rather, I see it as an act of interiorization of the very system, which I understand and want to deconstruct. I think one of the reasons “Triangle” is still interesting today is the issue of control over public space, which is just as strong and present in neoliberal democracy as it was in communism. Today, surveillance is becoming so “natural” that we hardly notice the ideology behind it.

«Visual art at that time was not recognized as a relevant discourse, and my work became the subject of local (feminist) critique only much later, in the 1990s»

GE: The exhibition ‘Women’s House’ is divided into two segments and draws upon archival materials. A significant portion of the exhibit features the stories of other women, specifically detailing the histories of these individuals. How would you characterize the role of women during the period of former Yugoslavia?

SI: It is always important to remember that as soon as 1978, an international feminist conference was organized at the Belgrade student cultural center by women from Ljubljana, Zagreb, and Belgrade, under the title COMRADE-SSE WOMAN: The Women Issue? It was the first conference on this topic in socialist countries, where, in spite of the officially egalitarian policy, patriarchal culture was very much alive and present in real life. Naturally, the organizers were immediately attacked by the official Yugoslav women’s organizations whose criticism was based on the claim that such a feminist stance was superfluous in our society, which had already “overcome” gender differences in the Socialist Revolution. The same year, a group of women scholars from Zagreb founded the Women’s Section of the Sociological Society of the University of Zagreb, “Woman and Society,” and they started to systematically engage with feminist theory. Although I already had the chance to see some feminist art in foreign magazines and at exhibitions in Graz at the time, the fact that I was able to listen to and read “our” feminists was extremely empowering for me. However, visual art then wasn’t recognized as a relevant discourse and my work became the subject of local (feminist) art critics only much later, in the nineties.

«Violence against women is, unfortunately, a “universal” – not in the sense of a “transcendent” characteristic… but from the perspective of a shared ‘universal’ condition that women experience in patriarchal societies. Violence against women is not limited to any class, race, or religion. In this work (“Women’s House”), I wanted to redesign the “universal”»

GE: ‘Women’s House’ series, which began in 1998 and continues to this day, includes the stories of women living in shelters for survivors of domestic violence. The parallel between women from different historical contexts—such as those affected by the Second World War and contemporary women—seems to reflect an ongoing ‘battle’ that has often gone unacknowledged. How do you view this comparison?

SI: I consider Women’s House a work in progress, it is a long term project. You may say that the project bears witness to the continued and unceasing level of violence against women in our societies, West and East, North and South – the cases may have a “local” character, but the “universal” is the level of violence. Violence against women is regrettably a “universal” – not in the sense of a “transcendent” characteristic – since the reasons for this violence vary hugely – but in terms of a common “universal” condition which women experience in patriarchal societies. We know that violence against women is not confined to any class, race or creed. In this work I wanted to redraw the “universal” in such a way that, while seeing the particular cases, we are forced to reflect on the values in our own culture and society instead of merely distancing ourselves from this problem as something that happens to “others” or in “other cultures”.

My “battle” in the 1990s was against the collective amnesia regarding the antifascist tradition which was present in Croatia. It was a subject of my work GENXX. The work consists of textual interventions on advertising photos featuring famous fashion models. On each image the text that introduce the name and the surname of a National Heroine from the anti-fascist struggle of World War II, along with her age at the time of her death. These National Heroines (and the same goes for National Heroes), had ceased to be an inspiration or role model for the younger generation already in the late 1980s. I like to think that GENXX advertises the values the National Heroines stood for: dedication to the ideals of social justice and equality, but also the women who participated on equal terms in public affairs and politics, unlike the attitude of the Croatian nineties which stressed family values and motherhood as the only proper areas for women.

GE: Looking back to the early stages of your work as a pioneer in video, performance, and conceptual art in Yugoslavia, what challenges did you face in creating art during that particular period?

SI: In the early 70’s there was no video equipment which was available for the artists so the “promises” of the “3/4 Inch Revolution” which were coming from USA sounded quite strange to us. In 1974. I discovered that one primary school in Zagreb just bought the equipment for educational purpose so I went there and managed to get the permission to use their equipment for half an hour. There I made my video “Sweet Violence”. I was inspired by Guido Guarda, the Italian media critic who was first to use the term “dolce violenza” . In his text he is reflecting on television as a powerful tool which can “sell” even a president to his country. I placed the black tapes over the television screen while recording the “Economic Propaganda Program” .It was indeed the simplest and the most effective way to disconnect viewers from the “sweet violence”, the violence committed in a tender, endearing way and thus even more efficient in its damaging effect.

«Art is only useful if it preserves its characteristics, its darkness, its ability to disturb, to penetrate the unconscious; if it reveals something that we experience every day, but have never truly recognized»

GE: Artists are often regarded as catalysts for revolutionary thought, challenging various systems and norms. In your opinion, does an artist have a responsibility to be politically engaged and to actively contribute to social change?

SI: I always say that everything we do has a political charge and the division between politics and aesthetics is entirely erroneous. From the beginning I have repeatedly asked myself what my position in the social system is, my relationship with the system of power, domination, exploitation and how I can act and react “meaningfully” as an artist. The “political” or “activist” attitude is the result of this dilemma: I want to be deliberately active rather than just a passive “object” of the ideological system. But I will also repeat: art is only useful if it maintains its strangeness, its darkness, its ability to disturb, to tap into the unconscious. if it discovers something we are witnessing everyday but never did recognize.

«Changing the world means ending the class society that created oppression and exploitation from the very beginning»

GE: What is the relationship between art and feminism in your practice?

SI: From the beginning in my art practice I had consistently dealed with feminist agendas, questioning and subverting the hegemonic codification of gender, representation of women in the media, and, through my work, constructing the paradigm of woman as the political subject. But the liberation of women has to be connected to a wider movement for human emancipation and for working people to control the wealth that they produce. That’s why women and men have to fight together, to change the world is to end the class society which created oppression and exploitation in the first place.

GE: You have previously collaborated with the National Gallery of Kosovo in presenting the exhibition “Women’s House”. From your current perspective, how do you assess the state of artistic collaboration in Kosovo?

The collaboration with NGK in making the exhibition “Women’s House” was for me an amazing experience and i will remember it as the happiest moment in my art practice in 2024. I was impressed by incredibly committed, professional and creative engagement by NGK team. I am also very grateful to designer Nita for her energy, creativity, and thoughtfulness she contributed.

photo by: Zvonimir Dobrović /Gazeta Express

Të tjera nga rubrika

Doli numri i ri i Revistës Letrare “Jeta e Re”

Festivali i Letërsisë “Polip” me edicionin e ri

Alenka Bartuloviq, mysafire e programit të ligjëratave “Leksione albanologjike”

Ekspozita “Rimendimi i totemëve” nga Genc Rodiqi

Galeria e Ministrisë së Kulturës kalon në administrimin e Galerisë Kombëtare të Kosovës

Dita e librit – Gjendje e pakënaqshme e leximit dhe mbështetjes institucioanle të librit

Te fundit

Edon Zhegrova i del në përkrahje Belgin Jasharit

ShKShMK njofton për operacion shpëtimi në Malet e Sharrit, nuk tregojnë për cka është fjala

Gjesti për Diellzën: E di që do ta takojë, do t’ia kthej të gjitha që ka bërë për mua

Gjendet mjet i pashpërthyer në Kaçanik, KFOR rekomandon sigurimin e tij sepse mund të shpërthejë

Stubëll: Koncerti “Festat i kemi bashkë” sjell Pashkët në nota klasike

BE ndërmerr veprime për substancat e dëmshme në lodra, çfarë po bën Zvicra?

✕

Edicioni

Edicioni

t7 live

t7 live